Table of Contents

ToggleMount Fuji has been at the center of Japanese spiritual practice for thousands of years with countless individuals summiting the volcano in pilgrimage. Although the volcano is now considered dormant, in the past it was both a site of reverence and source of apprehension, much like the gods being worshipped in ancient times.

As a result of the immense impact this infamous volcano had on the lives of the people who lived within its wake, like many mysterious forces, folktales were created as a way to explain the natural phenomena. While many Japanese myths take place in imaginary or unnamed lands, there are quite a few that mention the mountain specifically. Let’s take a look at some of the most famous folktales that feature or take place around Mount Fuji.

The Birth of Mount Fuji

Although the exact origin of the name Fuji remains unknown, it is thought that it comes from either the Ainu fire goddess Fuchi or a possible kanji reading meaning “eternal”.

The story of how the mountain was created takes place on the barren plains of Suruga where there was once a woodsman called Visu. He lived there with his wife and children, but life was hard and every day a struggle. That evening, as Visu lay down to sleep, he was startled at the sound of an incredible crack coming from deep within the earth. Immediately panicked that an earthquake had begun and his family was in danger, he rushed his wife and children out the door of the hut where they were greeted by the most spectacular sight of Mt. Fuji, which had suddenly emerged from the soil. In awe, Visu called the mountain Fuji-yama, the never dying mountain. And thus, the lands surrounding the mountain were transformed into fertile ground where Visu and his family could live a comfortable life from then on.

Discover Japan’s rich culture via its regional culinary traditions from the Fuji area and beyond: Sakuraco sends traditional sweets & snacks from across Japan to your door.

The Goddess of Mount Fuji

In the Shinto religion, the goddess of the mountain is called Sengen or Konohanasakuya-hime (often shortened to Kono-hana). The daughter of the god Ohoyamatsumi, and wife to the god Ninigi, she is also the goddess of blossoms with her symbol being the cherry blossom, representing the fragility of life on earth.

According to the mythology, the god Ninigi met Kono-hana along the shores of the sea and was enraptured by her beauty. He begged her father for her hand in marriage and eventually, seeing that Ninigi’s intentions were true, Ohoyamatsumi relented. Once married, Kono-hana soon fell pregnant which caused Ninigi to become suspicious. As a way to prove the child was his, Kono-hana ran into a burning hut declaring that any child of Ninigi would not be harmed. She gave birth to 3 sons: Hoderi, Hosuseri, and Hoori. Hoori is considered the grandfather of the first Emperor of Japan.

To this day, there is still a Shinto shrine dedicated to the goddess at the summit with ceremonies taking place throughout the year to appease her and to keep climbers safe.

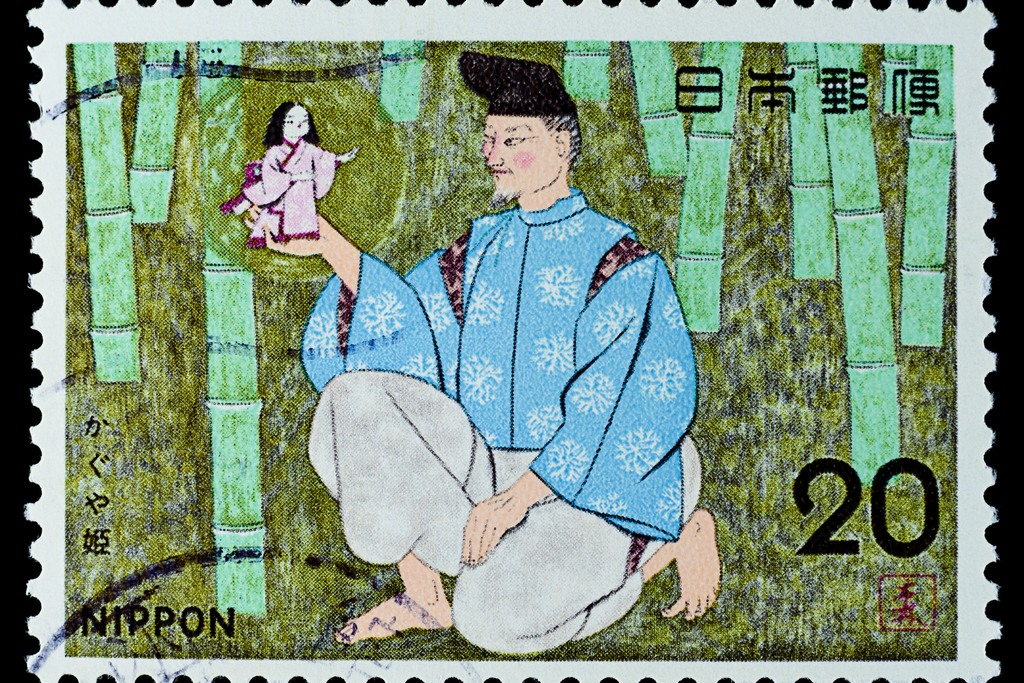

The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter

Also known as “The Tale of Princess Kaguya”, this folktale is the earliest example of the monogatari (fictional prose narrative) and was written around the 8th century. It tells the story of Kaguya-hime, a princess who comes from the moon who is discovered as a tiny baby by happenstance inside a bamboo stalk. She grows into a beautiful woman and challenges her suitors for impossible tasks before returning to her celestial homeland.

One of the earliest versions of the story mentions smoke rising from Mount Fuji which implies the volcano was still active when it was first written. The mountain had stopped emitting smoke as of 905 CE, therefore scholars surmise that the tale was first recorded somewhere around the late 9th century.

Fuji Mythology in Edo Japan

Like many other cultures, myths in Japan are often a combination of moral lessons and explanations for natural phenomena. With Mt. Fuji having played such a large role in Japanese culture as well as an imposing part of the landscape that could wreak havoc at any time, it is of no surprise that the volcano figures into so many legends.

What is quite interesting, however, is that there was a real surge in legends, poems, and songs celebrating Mount Fuji in the Edo Period (1603-1868). This is most likely due to the fact that the Tokaido Road was built at this time between Kyoto and Edo (modern day Tokyo) to facilitate the movement of both people and goods into the new capital. It is along this road that many people were able to view the mountain with their own eyes for the first time.