Much like a photograph, the iconic style of Japanese woodblock prints, or ukiyo-e, captured snapshots of life in Japan’s Edo era. Ukiyo-e (浮世) is a traditional Japanese print method that became popular in the 17th-19th centuries. The woodblock printing method originated in China, but it soon flourished as a unique method of printing images and Japanese art in Japan.

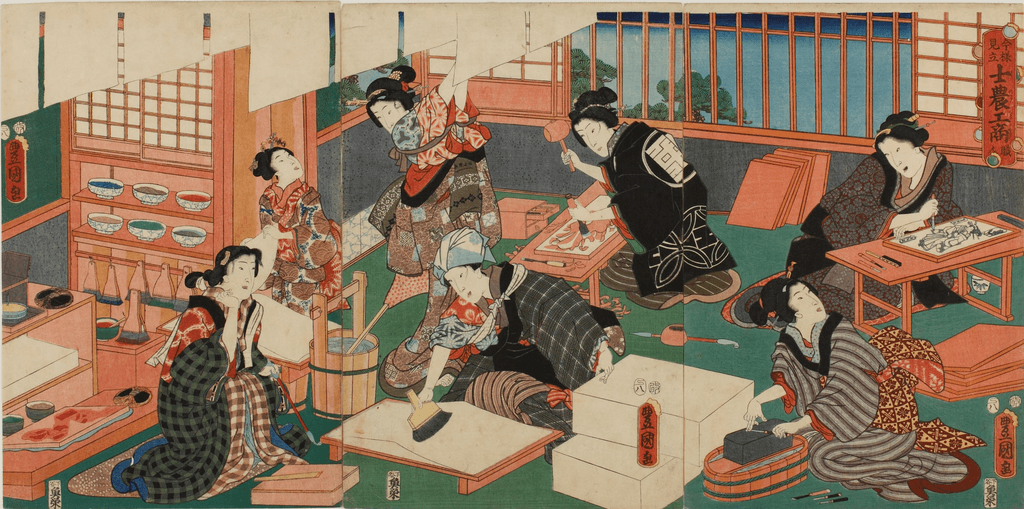

Artists recorded scenes from everyday life. They depicted landscapes, animals, and portraits of courtesans, actors, and sumo wrestlers of the time. The rise in popularity of ukiyo-e was due to a combination of circumstances. These circumstances resulted in a unique multidisciplinary art form. Ukiyo-e combined skilled craftsmanship, artistic expression, popular culture, and economic savvy.

Table of Contents

ToggleHow did artists make Japanese woodblock prints?

Generally, the artist carves an image onto a wooden block using a raised relief method in woodblock printing. They carve away areas of the image with no ink, leaving only the ridges to carry ink, similar to a hanko. This allows for separate printing of outlines onto textiles or paper. The artist would then send the design to a professional printer for printing. A publisher then made the ukiyo-e print available on a larger scale.

In the case of ukiyo-e, cherry wood (sakura) was the material of choice for woodblocks.

After soaking cherry wood in ink for long periods, it remains challenging, thus preserving the fine lines of the carved images. It is also hard enough to withstand the pressure of multiple presses without damage. An additional advantage was its beautiful grain, which would sometimes be imparted onto the printed design. This was important, as the effect lasted only for the first few prints as woodblocks became worn, increasing demand for the earlier “limited edition” prints.

Ukiyo-e is unique as a Japanese art form. Unlike other Japanese products like a sword or piece of pottery, which may be the work of primarily one master artist, Japanese woodblock prints rely on multiple industries and skills to create a finished product. An artist first produced an original design, which a carver transferred to a woodblock. This would then be sent to a printer professionally printing the design. A publisher was then needed to make the ukiyo-e available in large numbers economically.

Attitudes about Japanese Woodblock Prints in the Edo Period

The 17th through 19th centuries were a time of great prosperity in Japan. After many years of war, the Tokugawa shogunate ushered in the Edo era, a period of stability that allowed a wealthy merchant class to flourish. Their newfound wealth and safety lead them to seek new ways to enjoy their leisure time and spend money. Japanese artists in the pleasure districts, such as kabuki and geisha, benefited greatly from this new influx of cash and interest.

As Japanese society became increasingly interested in worldly pleasures, the term “picture of the floating world” or “ukiyo-e” came to be used to describe this shift in the public’s attitude towards life. This more relaxed approach to life was responsible for the development of ukiyo-e during the Edo period and many other art forms.

Artisans and craftsmen in the lower strata of Japan’s social system also experienced an improvement in their quality of life. They became more economically comfortable as wealthy merchants spent more money on wares. Because of this patronage, artists could devote more time to refining their skills and travel to seek inspiration in the relative safety of the Edo period.

Are you interested in discovering more about traditional Japan? Check out Sakuraco! Sakuraco sends traditional Japanese sweets, snacks, and tableware from across Japan to your door so that you can enjoy the experience!

Ukiyo-e Artists and Schools

In the 1600s, Hishikawa Moronobu created the first black and white Japanese woodblock prints. In step with the times, artists created prints of beautiful women inspired by famous geisha and courtesans. As the number of ukiyo-e artists increased, people could recognize them by their specific styles. Many artists still use these styles today.

As these differing styles attracted students, schools carried the name of their original artists. Ukiyo-e styles varied by region, like the now famous “Osaka school.” There are numerous ukiyo-e schools, but some have become more famous over time.

Hishikawa School

Hishikawa Moronobu started the Hishikawa school in the 17th century. The artist and school alike are known for merging multiple ukiyo-e styles into one distinguishable “look.”

Utagawa School

The Utagawa school was the largest of the 19th century. Utagawa Toyoharu, whose specialties were beautiful women (bijinga), founded it. Utagawa’s art uses foreground and background, a familiar aesthetic in Western art at the time. He introduced the style to the Japanese art world as ukiyo-e.

Hokusai School

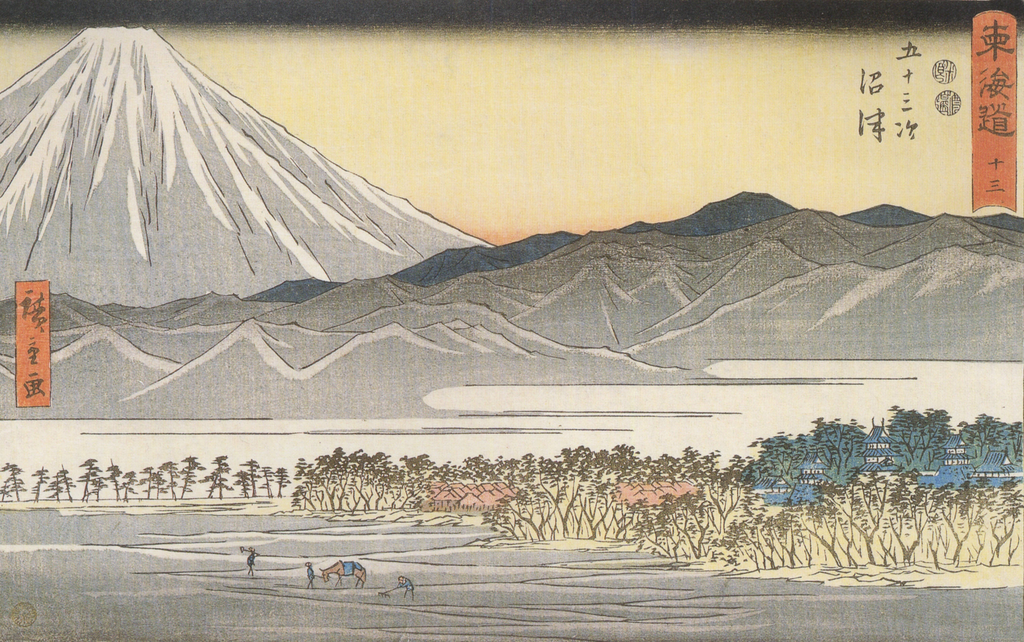

The Hokusai school of the 1700s and 1800s honors Katsushika Hokusai, who is most famous for creating his series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. This series includes the legendary piece “The Great Wave off Kanagawa.” Another piece from this series South Wind, Clear Sky, or Gaifu kaiseki (casually known as Red Fuji), hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Hokusai redirected the focus of ukiyo-e from portraiture to landscapes. This was a direct result of the prosperity and safety of the Edo period, which afforded the lower classes of Japanese society more opportunities to travel within Japan.

Ippitsusai School

Ippitsusai Buncho mastered capturing recognizable facial features in the 18th century. Before this school, the faces of kabuki actors in woodblock portraits were essential and bore little resemblance to their subjects.

Suzuki School

Suzuki Harunobu focused mainly on beautiful women and erotic images (shunga) in the latter half of the 18th century. He was the first to use multiple woodblocks and introduce full-color ukiyo-e. Before this innovation, Japanese woodblock prints were limited to three colors or less. He is also responsible for applying the technique to the woven fabric as brocade images (nishiki-e).

Utagawa School

Utagawa Hiroshige was the last great ukiyo-e master. He was a student of the Utagawa school in19th century. After a journey along the Tokaido road, he created his most famous series of woodcut prints, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. He then started on another popular series, The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido. Though he died before completing this series, his son, Hiroshige II, followed in his father’s footsteps and completed the series of woodblock prints.

The ukiyo-e style is still alive and well. Though printing methods have changed, the style is still used in advertising and art in Japan and internationally. Through the collaboration between artists and industries, we thoroughly understand life in the Edo period. And the “floating world” can still be enjoyed through these skillfully rendered prints.