Japanese wasabi is an aromatic green root often in Japanese cuisine, particularly sushi. Because of its popularity, many are curious about this peculiar root’s long and fascinating history. In any case, wasabi is a centuries-long staple due to its unique flavor and medicinal properties.

It was first cultivated in Japan over a thousand years ago and has since become an integral part of Japanese culture and cuisine. Today, wasabi people enjoy wasabi worldwide, and its distinctive taste and aroma continue to captivate food lovers everywhere.

Table of Contents

ToggleJapanese Wasabi Origins

Although the exact time when people in Japan first consumed wasabi is unclear, archaeological sites dating back to 14,000 BC have revealed evidence of them eating the plant. They may have used wasabi to prevent intestinal disorders, as mixing it with food enhances its shelf life.

Traditional medicine continued to employ the plant even many years later. Old garden sites regularly uncover wooden medicinal labels. The first record of the word “wasabi” was from 7th-century Nara Prefecture.

The Honzo Wamyo, Japan’s oldest chronicle of traditional plant medicine, mentions wasabi. Its decisive nasal action helps with respiratory disorders and is a natural ointment preservative. Wasabi became a vital component in many medical preparations as a result.

Japanese Wasabi Farming

People generally consider the Abe River near Utogi, Shizuoka, the birthplace of wasabi growing in Japan. Many residents of the area routinely picked and used the plant. Wasabi farming became popular in the 1500s by the shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu. According to historical documents, the Tokugawa received the plant and marveled at its many benefits.

In addition, the wasabi plant’s physical beauty impressed the shogun as well; wasabi leaves resembled the shogun’s family sign, the leaf of the Asarum or wild ginger plant. Taking these coincidences as a divine sign, Tokugawa ordered his staff to plant wasabi at Suruga Castle.

Methods

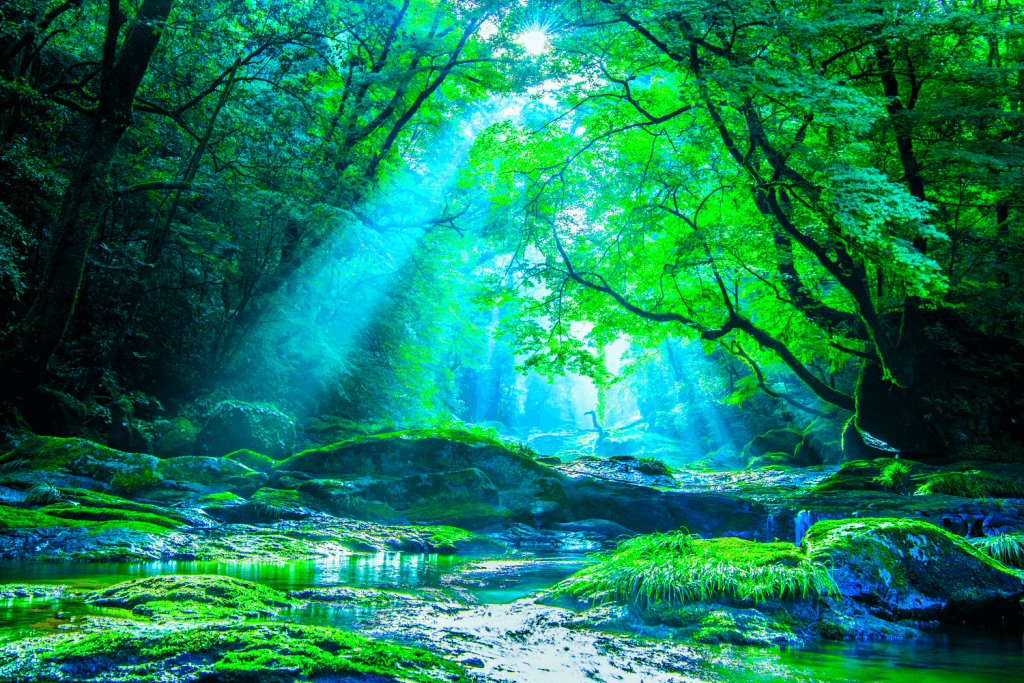

Wasabi grows best in narrow mountain valleys, as the name suggests. The plant is tough to cultivate, especially on a large enough scale for commercial farming. Its roots require a steady flow of chilly water to flourish, which mountain streams provide. Water must not be overly acidic or alkaline. It can also be shallow enough.

The roots require rocks to cling to, but they also require soil and organic materials, such as rotting leaves, to give nourishment. Wasabi is resistant to cold yet easily harmed by heat. Also, the air must be pretty humid. Because of these unique requirements, the plants do not grow well outside of mountain settings.

Furthermore, because wasabi grows in water, it’s susceptible to many pests that thrive in damp forest conditions. Unfortunately, farmers do not use pesticides to control such pests since the chemicals may contaminate the water source downstream.

Because of these difficulties, farmers closely maintain these wasabi plants and inspect them throughout their lifecycle. Moreover, due to the steep terrain making employing machinery impossible, growers must frequently travel long distances into the mountains to care for the plants. Once collected, the workers must haul the wasabi down the mountain. Wasabi farming uses traditional methods as a result of these harsh environments.

Are you looking to experience the best samplers of local Japanese cuisine? Check out Sakuraco! Sakuraco delivers traditional Japanese snacks, teas, sweets, and snacks from local Japanese makers directly to your door so you can enjoy the latest sweets directly from Japan!

Traditional Japanese Wasabi Cultivation Methods

As wasabi farming expanded throughout Japan, various regions developed their farming techniques to suit local conditions. Different farming practices are widespread among streams within the same valley.

The keiryu (渓流) or “mountain stream” style is the original wasabi growing method, and it initially began in Shizuoka Prefecture. Over time, this approach has spread to other locations, including Yamaguchi, Okayama, and Hiroshima.

Farmers build stone walls of the keiryu style along stream banks, following the natural course of the waterway. They then directly plant the wasabi in the riverbed and meticulously mend the stone walls by hand when necessary.

Different types of growing methods quickly evolved. The tatami, or “paving stone” style, is a version of the keiryu style that has become the most popular in Shizuoka. Farmers build stone walls across the stream, place sand behind the walls to form steps, then plant with wasabi. This technology allows for greater control over the depth of the water and further filters the already immaculate mountain.

As wasabi farming expanded to the lowlands, cultivation techniques also evolved. The heichi shiki style uses spring water rather than mountain streams. Farmers flood flat terrain like a Japanese rice paddy and plant wasabi in shallow water.

Although the conditions are good, this method allows wasabi to develop on a larger scale. The large, flat farms allow for more wasabi production and make it easier to use machines. The Daiso Wasabi farm is the most well-known example of this approach in the Nagano area.

Types of Japanese Wasabi

Not only is wasabi a condiment, but it is also a delicacy. Because of this, wasabi varies in appearance and taste depending on its origin, form, and availability. Here are the different types of wasabi that people enjoy around the world.

Hon Wasabi

“Hon” (本) means “original” or “natural” in Japanese, and it refers to 100% wasabi root. It has a fresh, natural taste not found in other forms of wasabi. It is the highest quality one can buy and, as a result, the most expensive. Naturally, it is available in high-end sushi restaurants.

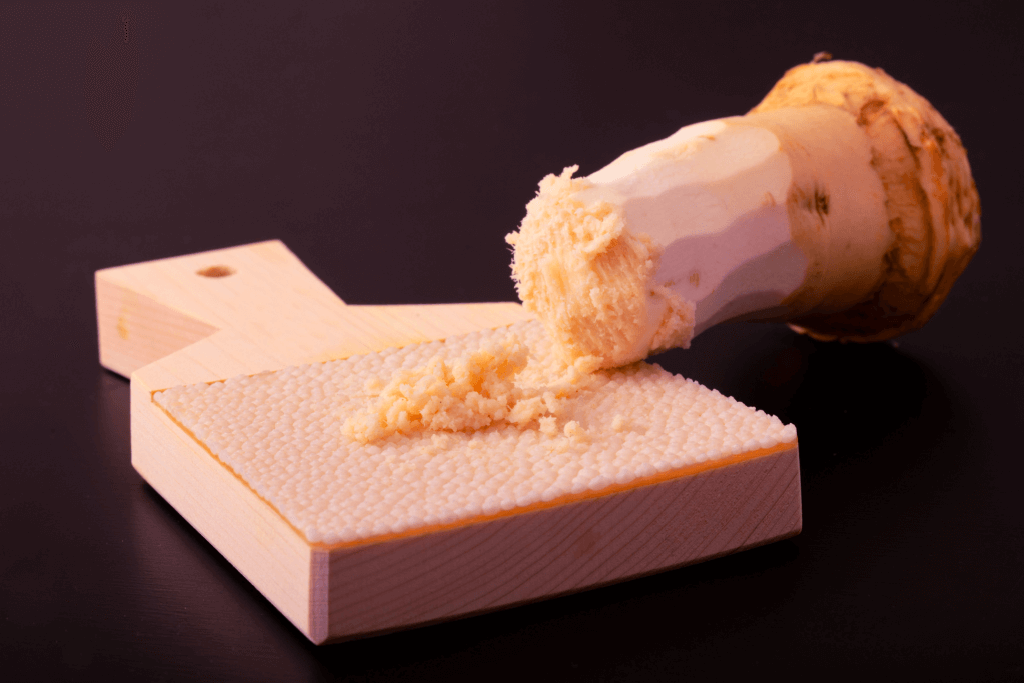

Nama Wasabi

This is hon wasabi that has been recently grated into a paste. “Nama” means “raw” in Japanese and indicates that the wasabi paste contains no additives. It’s best to use this condiment as soon as possible, or it’s no longer “nama” or “fresh.”

Yama Wasabi

The cold weather of Hokkaido results in the wasabi root is white instead of the usual green. In addition, this wasabi is also spicier as a result, and nama wasabi made from it is said to be spicier still. It is rare outside of Hokkaido, where it is considered a local delicacy.

Sabi Wasabi

Sabi wasabi combines wasabi, horseradish, and green food coloring. It sometimes even contains mustard. It is a cheaper product that approximates the taste of wasabi. Because it can be mass-produced using many products and is less spicy than real wasabi, it is the most common form of wasabi. It is usually the type of wasabi found on supermarket shelves.

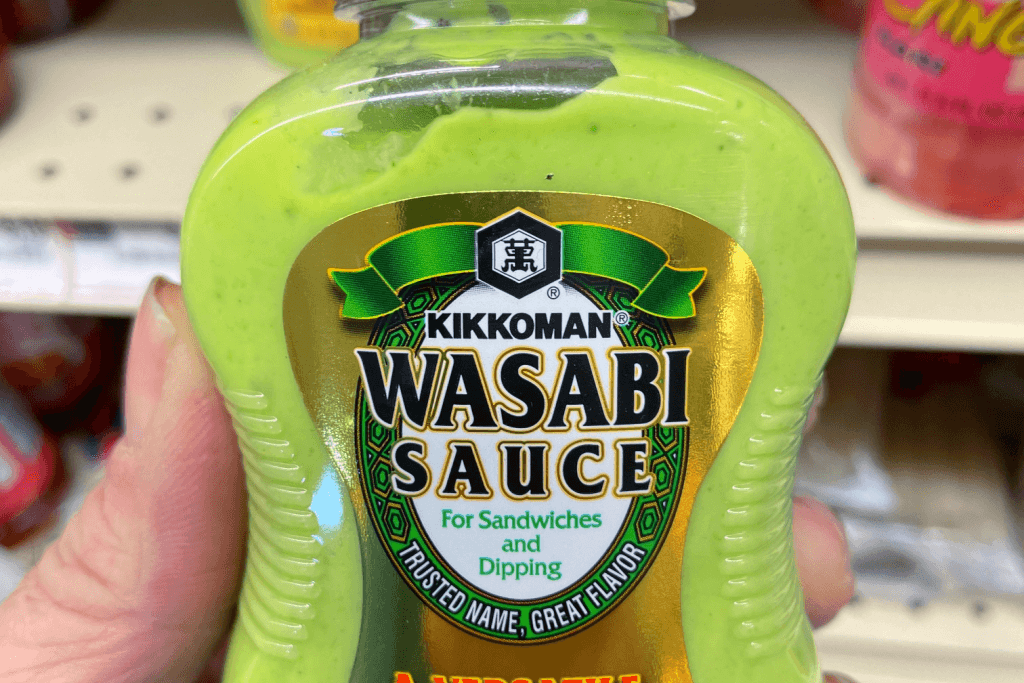

Western Wasabi

Seiyo (西洋) wasabi, or “Western wasabi,” is usually made from horseradish, mustard, and food coloring and may contain no wasabi. Real wasabi can be difficult to find outside Asia, so this sauce is sold as a substitute in western markets. It is also better suited to such markets, as foreign customers sometimes do not like the taste of authentic wasabi.

It is a difficult time for the wasabi plant in Japan. Today, the number of wasabi farms in Japan is gradually decreasing. The demand for wasabi in Japan is far more than local farms can supply. Attempts have been made to produce the critical root on a large scale, but this hasn’t proved easy. Mainly because the specific conditions required for the plants’ growth result in lower-quality wasabi when grown outside of mountain areas.

Also, the amount of work required to farm wasabi causes some farmers to grow other crops. Increasing global temperatures mean farmers must hike even higher up the mountains to find the ideal conditions. That wasabi paste will likely become more and more common in the future.

Overall, the strong relationship between sushi and wasabi ensures that at least some farmers will continue hiking into the mountains to preserve the culture surrounding this vital root. Have you ever had Japanese wasabi before? Did you like the taste? What are your favorite foods to pair with it? Let us know in the comments below!