Origami paper, with its rare simplicity and endless potential, has become one of the most accessible traditional Japanese art forms. It requires no special equipment, training, or instructor, making it available to people of all ages.

All you need is a piece of paper, instructions, and patience. This art form can be practiced almost anywhere, and its transformative power has allowed it to evolve from a Japanese aesthetic to a globally embraced art form, transcending borders.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhere did origami paper come from?

When the paper first arrived in Japan from China in the 7th century, it used wood pulp fibers that did not respond well to folding. Still, people use it for writing and, more importantly, decorations at various festivals and rituals. Inevitably, Japan soon developed techniques to produce a paper that differed from those used on the mainland.

During the 11th century, Japanese artisans began experimenting with various plant fibers to create more durable paper. Among the plants used, the gampi tree, mitsumata shrub, and paper mulberry played vital roles in developing origami paper.

People soaked these plant fibers in water to thicken them, layered them into a single sheet, and coated them with plant mucous. As a result, they created Japanese-style paper, known as washi, which surpassed Chinese paper in durability and even found utility in clothing.

What is traditional origami paper like?

As the 11th century progressed, there was a paper renaissance in Japan. At the time, Chinese paper decorations were typical at ritual ceremonies. However, the new washi paper had two fascinating characteristics; it responded well to repeated folding and maintained these folds and shapes over time. As a result, decorative designs began to emerge, and it was only a short time before these became the standard for Shinto blessing and purification rituals at temples.

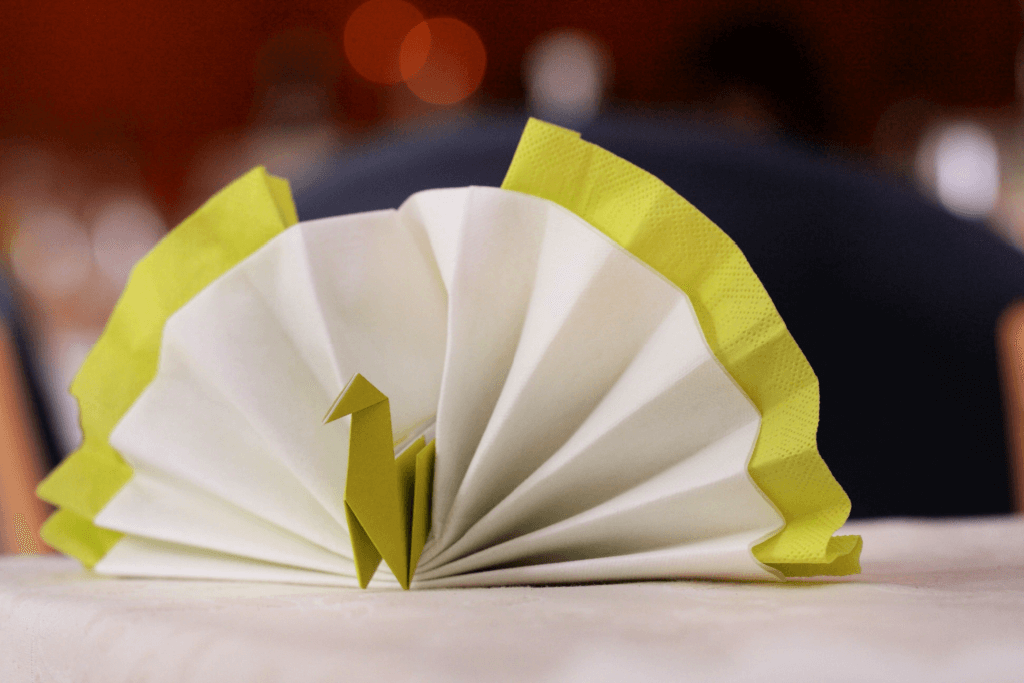

The form of origami known as girei or “ceremonial” origami has endured to this day in various forms. One is shide, the zigzag paper streamers commonly present at temples, roadside shrines, and on trees. Additionally, girei origami is for adorning money envelopes and sake bottles. These modest paper designs represent the surviving legacy of Japan’s earliest origami traditions.

When did origami paper evolve?

Over time, girei origami became the norm at ceremonies. Naturally, it was only a matter of time before the emperor noted this and formalized specific origami, noshi, for ritual use. In the 13th century, the samurai class, with its strict code and rules, were some of the first outside royal circles to use noshi when giving gifts at more social ceremonies like weddings. Many of these customs are still present today.

Throughout Japanese history, the samurai class has held a special status and has been widely admired. As a result, other elite classes, including members of the royal court, began adopting the gift-giving customs of the samurai. Therefore, using noshi, decorative folded paper strips gradually became more prevalent in formal settings.

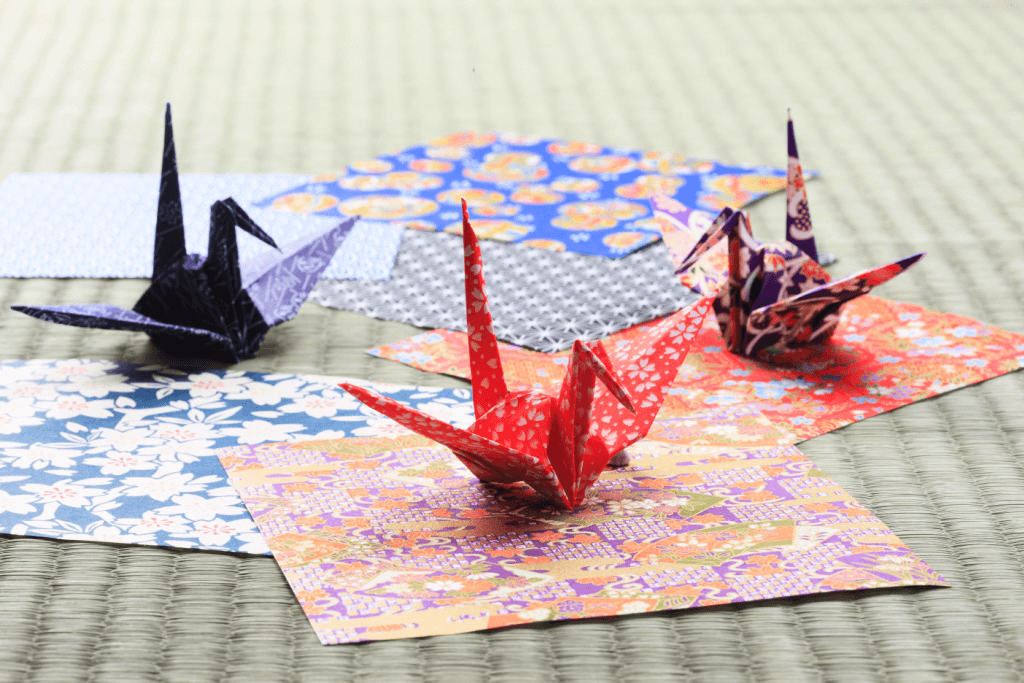

The increased popularity of noshi also led to further innovations, such as using wood blocks to print intricate designs onto paper. This technique led to the creation of yuzen washi paper, also known as chiyogami, renowned for its vibrant colors. Today, this colorful paper is inseparable from the art of origami.

What is chiyogami paper?

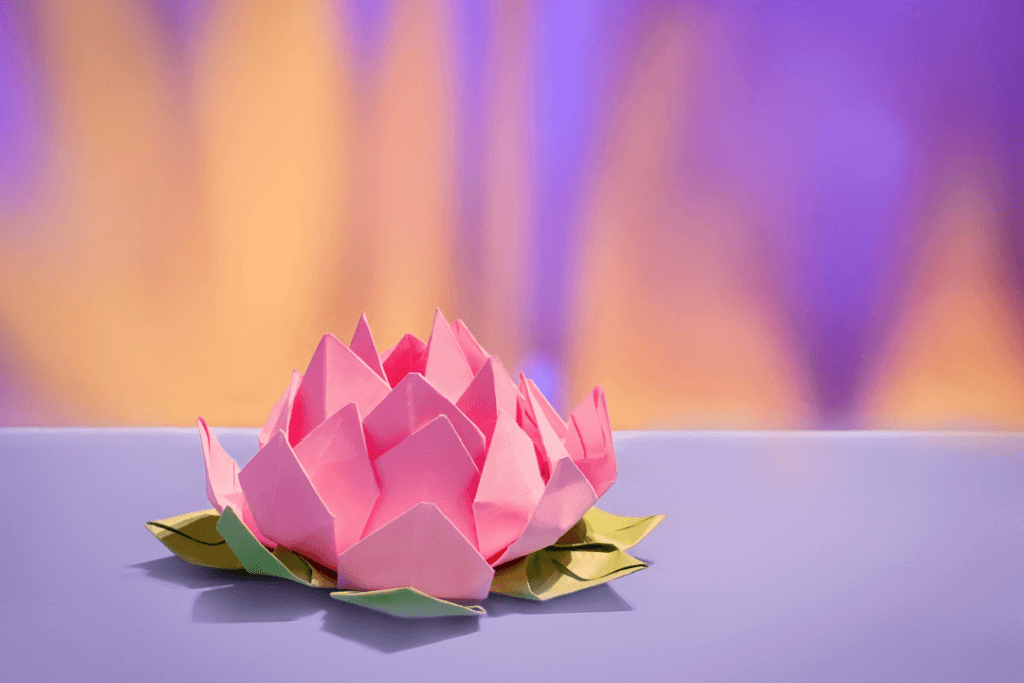

In the 14th century, chiyogami paper became more widely available to the general public. People discovered that this beautiful paper was suitable for decoration and made excellent standalone gifts. It became socially acceptable for people to fold colorful paper into shapes such as dolls, animals, and flowers, and they would present them as gifts. During this period of heightened creativity, the crane was the most popular design.

Believers attribute the origination of the folded crane, known as orizuru, to this time. Today, people engage in the recreational practice of origami, referred to as yogi origami, meaning “play” origami, to distinguish it from more traditional or ceremonial origami.

Are you interested in more traditional Japan? Check out Sakuraco! Sakuraco delivers traditional Japanese snacks, teas, sweets, and snacks from local Japanese makers directly to your door so you can share more of Japan’s rich culture.

What are some origami secrets?

Not everyone in the 16th century saw origami simply as a custom or form of recreation. Monks and priests, especially, continued to perfect art as a form of meditation. In 1797, a Buddhist monk named Gido from present-day Mie Prefecture wrote what many believe to be the first origami book. Hiden Senbazuru Orikata, “The Secret to Folding One-thousand Cranes.”

The book contained a collection of 49 origami designs along with written instructions for their construction. This book’s most popular origami creation is the Hyakkaku or “One hundred cranes,” where numerous connected cranes use a single piece of paper.

How did the art form spread?

Although revolutionary, the instructions in Gido’s book proved difficult to follow for some. This all changed in 1954. Akira Yoshizawa is the single most influential contributor to origami. His published collections of origami shapes included instructions, lines, and other symbols for specific folding techniques.

Previously difficult-to-describe techniques such as “rotate” and “inflate” were now more easily understood by the novice practitioner. And when Japanese immigrants began relocating to the United States later in the twentieth century, they took these instructions with them—the export of this written knowledge transformed origami from a local pastime into a legitimate international hobby.

What is origami today?

Origami is now famous all over the world. One of the largest hobby groups outside of Japan, OrigamiUSA (OUSA), has over 1700 members worldwide. In Japan, Gido’s hometown of Kuwana City in Mie prefecture lists the origami creations in his book as invaluable cultural properties. The city acts as both curator and ambassador. It protects his origami legacy and trains individuals to reproduce his works and preserve his original designs correctly.

Traditional washi paper itself is an internationally renowned product sought after by origami and stationery enthusiasts. It is still used in shoji screens both in Japan and abroad. Its strength and lack of added chemicals make it uniquely suitable for repairing fragile museum pieces such as paintings and old textbooks. In 2013 washi paper was recognized by UNESCO as a form of world heritage.

The simplicity of origami has ensured its survival throughout the centuries. Not only has it persevered as an art, but it has expanded beyond its original uses and borders to gain worldwide recognition. Origami has maintained its original form and evolved into something new, like a simple paper folded into something new.