In Japan, the mid-autumn festival is tsukimi or otsukimi, which means “moon viewing” in Japanese. The festival is held on August 15th of the Japanese lunar calendar, as it is said that the moon looks the most beautiful and bright. Around this time, people offer tsukimi dango to the moon to appreciate the harvest. Though custom originated in China, it developed uniquely in Japan.

Tsukimi dango are plain white rice dumplings. During this time, under a full moon, Japanese people celebrate the harvest and marvel at the passing seasons. It’s a straightforward holiday treat, so keep reading if you want to celebrate this festival with us!

Table of Contents

ToggleTsukimi Dango’s Origin

The mid-autumn tsukimi festival’s origins are rooted in China, from which the tradition traveled to Japan during the Heian period. During this era, the aristocratic elite did “moon-viewing” the most, but it eventually spread amongst the common people during the Edo period.

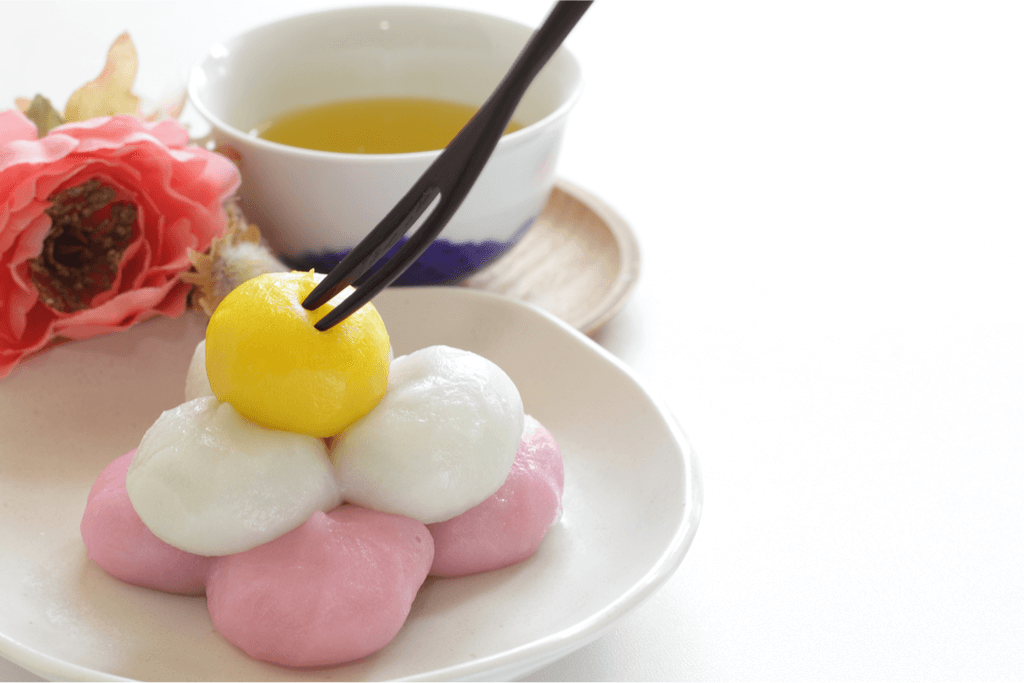

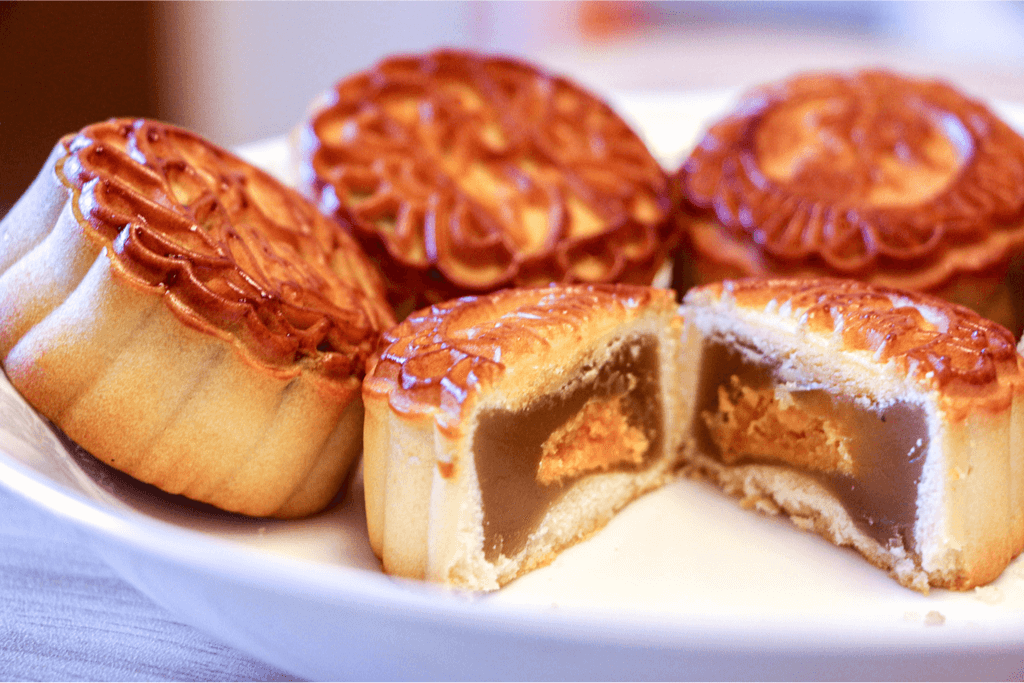

Inspired by the Chinese’s use of mooncakes, the Japanese crafted tsukimi dango, round white spheres that resembled the full autumn moon. People offer them along with vegetables from the autumn harvest, including potatoes, edamame, and chestnuts. Legend also says that the moon is the brightest on the fifteenth night of the lunar calendar. As such, people arrange tsukimi dango in a pyramid of fifteen.

What is Tsukimi Dango?

Tsukimi is the moon viewing festival which takes place mid-autumn, usually falling between mid-September to early October. It’s to celebrate a good harvest as well as good health. Dango are Japanese rice dumplings, these traditional Japanese sweets are chewy and delicious.

Putting it all together, tsukimi dango are round dumplings or mochi dango that you traditionally eat in Japan during the moon-viewing festival. While they sometimes come in different flavors or glazes, tsukimi dango uses it in the simplest form, so they’re effortless to make! Because these are plain dango, they only have a natural sweetness from the rice, but you can always add some sugar if you prefer them a little sweeter.

Looking to enjoy more unique and traditional Japanese holiday treats in the comfort of your home? Check out Sakuraco! Sakuraco delivers traditional Japanese snacks, teas, sweets, and snacks from local Japanese makers directly to your door!

Tsukimi Dango (Moon Viewing Mochi) Recipe

Ingredients:

- 50g (around 2oz) sugar (this is optional, depending on how sweet you like your dango)

- 250ml (one cup) lukewarm water (use warm water to hydrate the rice starch)

- 200g (3/4 cup and 1 tbsp) rice flour (make sure to use the sweet kind, which is labeled shiratamako or joshinko)

- 50g (around 2 oz)glutinous rice flour

- Kabocha pumpkin (you will need around 10 ml (2 tsps) of mashed kabocha)

How to Make Tsukimi Dango

- Bring the water to a boil and dissolve the sugar.

- Turn off the heat and gradually add the rice flour and the glutinous rice flour. Mix to distribute the liquid evenly. Eventually, the flour mixture will form large clumps.

- Transfer to a working surface and knead until smooth.

- Make the dough into a ball and divide the dough into eight (8) equal parts. Then divide each part into two (2) balls (20 grams each).

- Divide the dough into 15 equal pieces and roll each of those small into small, round balls.

- To make two (2) yellow balls, prepare 30 grams of dough and mix in 2 tsp mashed kabocha.

- Combine the kabocha and dough. If the yellow color is not intense, you can add more mashed kabocha, but you also need to add more flour to be dense.

- Shape into a smooth round ball. If you need help making it smoother, tap your finger in water and apply a small amount.

- Roll 15 white balls and two (2) yellow balls in total.

- Place a damp cotton cloth in a steamer and put the balls on it.

- Steam the steamer over medium heat for about 15 minutes.

- Wrap the lid with a cloth to prevent water leakage. Then, slide the lid of the steamer to control the temperature.

- Before transferring into a tray, let it cool for a while (if you wet the tray, the dumplings won’t stick).

- Decorate them on the sanbou (wooden stand) by placing nine (9) balls on the bottom of the pyramid, and four (4) balls on the top of the bottom layer.

- Lastly, place two (2) yellow balls at the very top, which represent the moon.

Have you tried to make tsukimi dango at home? Share your tips for a perfect tsukimi dango recipe in the comments below!